Since the brutal sweep of national media layoffs and budget cuts began earlier this year, Hawaiʻi organizations continue to stand strong against the current.

While no major layoffs have been reported at the state’s larger media companies thus far, thousands of jobs have already been slashed at leading news outlets across the continent, such as the Washington Post, Gannet, CNN, BuzzFeed, NPR and Vice.

In an effort to bring recognition to local news, U.S. Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaiʻi introduced a resolution last month that would declare April as “Preserving and Protecting Local News Month.”

The Hawaiʻi Democrat, who has pushed for local news legislation in the past, stated in a release that he hopes the designation will help “fight disinformation and strengthen communities.”

“As the industry continues to face newsroom closures and budget cuts, it’s critical that we support and recognize the irreplaceable public service local news provides,” he said in the release.

For several years, Schatz has urged Congress to examine the “role of local news gathering” in sustaining democracy in the United States and the factors contributing to the demise of local journalism.

According to research from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Hawaiʻi specifically has experienced a decrease of more than 40% in traditional newspaper production over the past decade. In 2019, newspaper circulation rates across the islands dropped by almost 300,000, further accelerating the loss of the number of journalism jobs in the state.

The resolution’s announcement comes at a time when local and national media outlets grasp for public support amidst layoffs and a potential recession.

More recently, NPR was the first major news outlet to go dark on Twitter, making headlines for closing all 52 of its feeds on the platform, after Twitter put a “state-affiliated media” label on NPR. The tech giant later retitled NPR as “government-funded," and then removed the label, which was not enough for NPR executives to change their minds.

In an email to an NPR reporter on Tuesday, Twitter owner Elon Musk suggested that he might reassign NPR’s Twitter handle to another organization or person.

Steven Waldman, the founder of Rebuild Local News and co-founder of Report for America, argues that NPR’s designation was “unfair” and “historically ignorant,” given that other news outlets, such as News Corp and Wall Street Journal, receive significant funding from government legal notices.

“If (Twitter is) going to do that, they'd better be consistent,” he said.Government interference

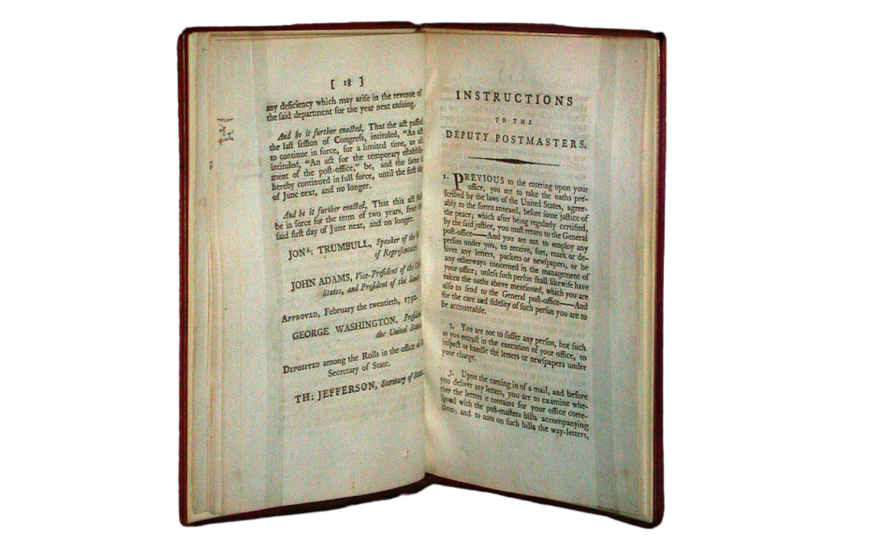

Historically, federal and local governments have provided subsidies for local journalism, dating back to the Postal Act of 1792. The act gave newspaper companies a highly subsidized postage rate to encourage the spread of information and to help facilitate democracy.

Waldman explained that NPR and Twitter’s dispute has sharply changed the meaning of the term “government-funded.”

“It’s like, almost a curse word,” Waldman said. “Like you say someone was government-funded, and that's like the worst insult. And that phrasing implies government control. The truth is, you can have and should have government funding for media. That's a good thing. If it's done the right way.”

Musk responded to NPR’s decision to leave the platform on April 12, with a series of tweets that drew a strong response from his followers in support of defunding NPR.

“Honestly? Defund the entire corporate press. They get too many freebies from the government anyway,” said a subtweet from Ian Miles Cheong.

“That’s the media for you…,” said another subtweet from Steve Ascher.

Less than a week after NPR left Twitter, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation followed, becoming the second major network to leave the social media platform, with executives stating that they are pausing posts after also being labeled a “government-funded media” source. The corporation has not unpaused its hiatus on Twitter since the announcement.

Waldman said he wishes the public would wake up “to how enormous a threat” the collapse of local news is in the U.S.

“And yet there is some hope because there's tremendous innovation and creativity going on right now,” Waldman said.

A drop in print circulation and jobs both nationally and in Hawaiʻi shines a light on new forms of storytelling currently working to keep the public informed.

While the resolution does not involve any sort of funding for local journalism, Schatz’s office told HPR in an email its purpose is to recognize the history and importance of media as a “public good” to serve democracy in the U.S.

The resolution was solely supported by Senate Democrats, including Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaiʻi. It was also endorsed by several major national news nonprofits that include the Alliance for Community Media, PEN America, the Native American Journalists Association and others.“Bookstores and libraries”

The idea of getting the government involved in the news should make a journalist’s skin crawl, said Waldman. However, he argued that there are ethical ways to weave the two together.

Waldman gives the example of bookstores and libraries. He started by saying that they perform different functions — libraries being taxpayer-supported to ensure that everyone has access to books, and bookstores being a business that makes money.

Waldman’s example gets at the point that local news may not be able to succeed without a combination of both profit-driven and public-interest-driven activities.

“There's going to be a mix of, hopefully, some kind of transformed commercial entities, nonprofit media, old and new, and then some government support,” Waldman said.

For Hawaiʻi, one media specialist suggests that rather than tying the two together, the government could work to “stimulate” an awareness of local news, so “long as there’s a clear cut-off.”

“I'm probably fairly negative because what I've seen happen in local media in Hawaiʻi is it just keeps diminishing,” said Chris Conybeare, president of Media Council Hawaiʻi.

“If there are ways to get government more involved in stimulating the environment for local journalism — that doesn't mean I want to see government telling local journalism, what to do,” Conybeare said.

That’s what Schatz’s resolution hopes to accomplish. However, Conybeare said he feels more can be done.

“(The resolution) doesn't really do anything specific,” he said. “I guess what I think is that we need a lot more than Senate resolutions.”