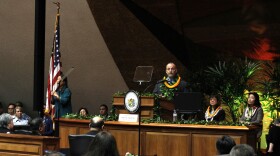

Gov. Josh Green has signed a law that gives the state Department of Transportation the ability to delay or deny entry and departure for any vessel that is known to have engaged in illegal deep-sea activity.

Deep-sea mining is the process of retrieving mineral deposits from the seabed. Over millions of years, scientists found that metals have built up on hydrothermal vents and underwater mountains in the form of nodules on abyssal plains.

These deposits contain zinc, gold, silver, cobalt, nickel and copper. Many of the minerals are used for the production of smartphones and rechargeable batteries — like those used for electric vehicles, solar panels and wind turbines.

The extraction and excavation of the materials, however, pose potentially serious threats to environmental and human health, according to Jeff Drazen, a University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa professor and deep-sea ecologist.

“We're talking about potentially very massive areas of seafloor being disrupted by mining. We've done a number of studies in these zones… there's a lot of organisms that require these metal deposits as habitat,” Drazen said.

Destruction of the habitats could mean a loss of biodiversity, something he says is integral to the survival of ecosystems.

The potential risks of mining don’t just occur on the bottom of the ocean, according to Drazen. When boats harvest and bring up the minerals, they also release unwanted mud and seawater.

“In the case of polymetallic nodule mining, we think that's going to be something on the order of 50,000 cubic meters of muddy water a day… that's going to hurt the organisms living there," he said.

He added that the turbidity could cause stress, make it harder for deep-sea fish who communicate with bioluminescence to communicate, and clog animal filter-feeding mechanisms. The return water could also contain dissolved metals.

“There is the potential for those metals to accumulate up food webs and to be in our poke bowls. And we don't know how much because we don't even know the concentration of the metals that might be discharged from these mining operations,” Drazen said.

Scientists have only recently begun studying the deep-sea, which makes it difficult to assess the potential impacts of mining or to put in place regulations to protect the marine environment, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Drazen said the ecosystems may never recover from these activities. “There's really a potential to lose species because it's such a big area of impact and removing habitat that takes millions of years to form. You can't just let it grow back,” he said.

The International Seabed Authority, which monitors activities in the seabed beyond national jurisdiction, has only issued licenses for the exploration of deep-sea resources, but there have been recent pushes to move forward with regulation on exploitation in international waters.

Drazen thinks Hawaiʻi sits front row and center for the deep-sea mining industry. The Clarion Clipperton Zone to the east and the Prime Crust Zone to the west of the island chain are the most sought-after mining areas, he said.

A bill banning the practice in Hawaiʻi's territorial waters was considered this past legislative session. Though it passed several readings, the bill was not adopted into law before the session closed.

“We are right in the middle of it. It's going to happen all around us,” said Drazen.