Was there really a Hawaiian Renaissance?

"Oh definitely, yes!" said University of Hawaiʻi Ethnic Studies professor Davianna McGregor. She is a member of the Protect Kahoʻolawe Ohana.

"At the same time that we were fighting to recognize the practice of Aloha ʻĀina, the Hōkūleʻa was organizing and then the whole movement for Hawaiian language started at the same time.

"We were looking at the loss of our language. And, you know, we were looking at the loss of our culture," McGregor said. "And when Kahoʻolawe happened and made the connection to our religion, and are our spiritual soul as a collective soul as Hawaiian people. This really again sparked the interest."

"At the same time that we were fighting to stop the bombing and recognize the practice of aloha ʻāina."

McGregor continued, "The Hōkūleʻa was organizing to revive and recognize Hawaiian navigational arts. And then the whole movement for Hawaiian language started at the same time with the Punana Leo, the preschools and then building into the Hawaiian language immersion classes.

McGregor said the Hawaiian Renaissance was anchored in state law by the last Constitutional Convention, held in 1978.

"The 1978 Constitutional Convention made it possible for our language, to be again the medium of instruction in the schools by making Hawaiian one of the two official languages for the state," McGregor said.

"The Hawaiʻi Constitutional Convention in 1978 was itself a part of that peaking of the Renaissance, in that it also made the teaching of Hawaiian history and culture part of the educational program, and recognized Native Hawaiian rights," McGregor said. "It set up the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, and it said that Native Hawaiians are one of the two beneficiaries for the ceded public lands trust. So the Constitutional Convention was critical to representing this move of Native Hawaiians to reclaim our culture, our lands, our language, and pivotal in promoting that to the next level."

"You go to Kahoʻolawe to establish the Makahiki, that's what Edith Kanakaʻole told us," says Dr. Emmett Aluli, physician, Medical Director at Molokaʻi General Hospital and Protect Kahoʻolawe Ohana member.

"Nalani Kanakaʻole wrote the protocol, wrote the chant. In 1981, we opened and closed the first Makahiki," Aluli continues. "That, simply put, calls Lono to bring his winds, to gather the clouds over Kahoʻolawe, to bring the rain to green the land, to raise the water table. At the same time to green ourselves to continue to struggle or be successful. And so all that works, and now we're celebrating the closure of our 40th anniversary."

"We feel most proud about reviving Hawaiian spiritual beliefs and practices," McGregor says. "It really is a reverence for land and a practice of stewardship for the land and the resources."

Aloha ʻĀina took root in the 1970s, and so did a new generation of local musicians. Kirk Thompson played soaring keyboards with Kalapana, a legendary band that helped forge a presence for Hawaiʻi's music on the national scene.

"There were a lot of talented groups that never got the break that we got, so to speak, so we had more of a duty to lead the way.

"Conquering Waikīkī was our first step in our younger age. It was a big deal at the time." According to Thompson, local pop and rock bands were not considered "good enough" to be booked in Waikīkī. Until Thompson and his band, Pacific, got some help.

"We broke the biggest club in Waikīkī. 1970, finally. Place was called the Red Noodle, right behind the International Marketplace, right behind Don Ho's Don was helping me out too," Thompson said.

Thompson says the same manager who developed Cecilio and Kapono, was looking for the next big thing. The four musicians had known or played together before, but Ed Guy formed the group eventually called Kalapana.

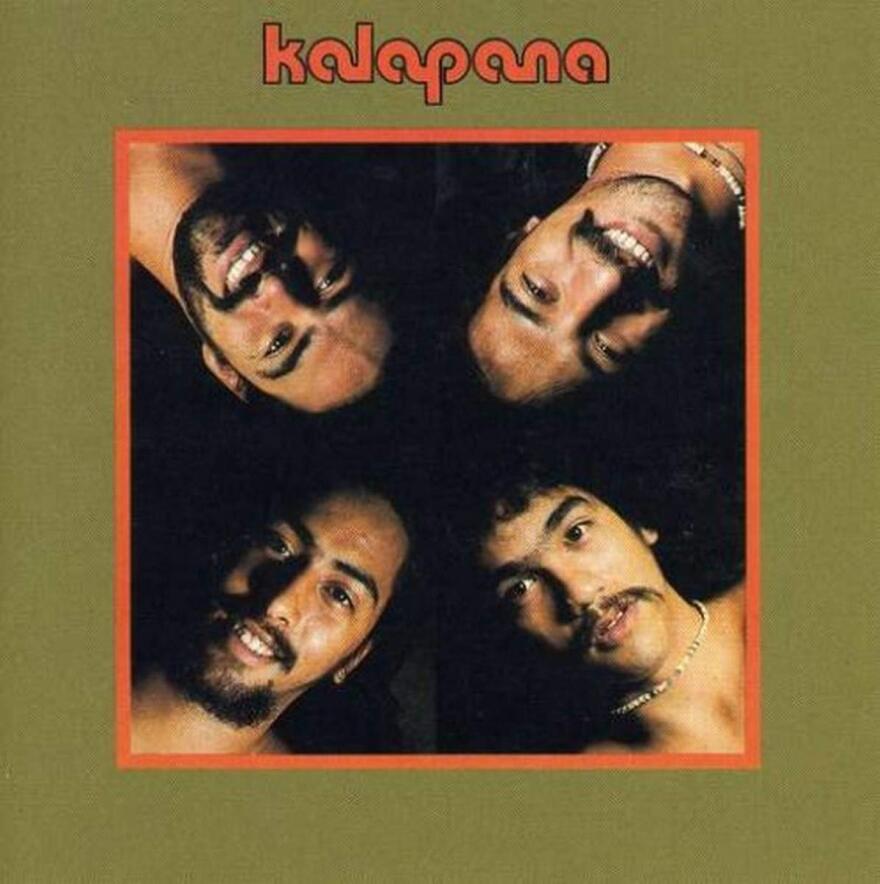

Founding members were Kirk Thompson on keyboards, bass and vocals, with singer/guitarists and fellow songwriters, Mackey Feary, David John (DJ) Pratt, and Malani Bilyeu.

"Electric was crossing over into acoustic and it was explosive," Thompson said. "In Kalapana, we crossed over. What happened was, we started out as acoustic. That's where Mackey and Malani came in because they were acoustic guys, so to speak. Me and DJ came off of electric but we could play acoustic, we could do anything."

Thompson said he and Pratt were assigned two songs for that first Kalapana album. Feary and Bilyeu each wrote three. The process flowed much like Bilyeu's song, Naturally.

In 1976, Kalapana's second album hit the National Billboard chart at No. 197, ahead of the Temptations and Tower of Power.

"Mackey was our Paul McCartney. Mack was extremely talented," Thompson said.

Feary, a charismatic lead singer, struggled with drugs and died by suicide in 1999. Malani Bilyeu was living on Kauaʻi when he passed in 2018. Pratt, one of the great guitarists of his generation, passed in 2021.

Thompson created the Honolulu Museum Contemporary Pop to honor those who raise Hawaiʻi's image on the music scene.

"Both C and K and Kalapana, we had a job to do," says Thompson. "Look at Bruno Mars, he's a perfect example of what I'm talking about. He believed in what he was doing. When I see him in the stadiums performing on the global scale, I'm so proud of him. He took it to the highest level anybody could. Any artist from any place in the world."

After years of wrangling over rights, that iconic first Kalapana album, is back in black vinyl at Aloha Got Soul, AGS, the local specialty records dealer. You can get it starting March 25, and AGS will hold a weekend-long release party at its shop at 2017 S. King St.

The weekend festivities will include official merchandise for sale, disc jockeys spinning Kalapana-related vinyl records, and a chance to hang with some of the ‘ohana and original band members. The shop is open from 12 to 6 p.m., with the event taking place from March 25-27.