Elmer Omar Pizo was born in the Philippines, where he went to seminary school, then worked in Saudi Arabia. Twenty nine years ago, Pizo immigrated to Hawai‘i and has worked in vector control, landscaping, carpentry, and security, all the while, quietly writing poetry. HPR’s Noe Tanigawa reports, his first collection is a window into Filipino life.

I met poet Elmer Omar Pizo at his home in ‘Ewa Villages, the family style neighborhood quiet, except for passing cars with souped up audio systems.

Elmer Pizo grew up in Pangasinan and spent some time in Ilocos Sur, Philippines. His mother was a elementary school teacher, his father was Dean of an Anglican-Aglipayan Seminary. When Pizo graduated from high school, he seemed to have a successful life cut out for him

Pizo: I went to the seminary trying to follow his footsteps. I left in the second year.

How did your father feel about that?

Pizo: He was upset and disappointed. He was expecting I would be like him too someday, but I fell in love with one wahine, so I got out. I regretted that decision because that wahine emigrated to Maui and she married another guy, so that’s the start of my failures, I think. I’ve been into a series of failures.

After seminary, Pizo went to agricultural school, farmed, taught poultry production, then, with wages low and options slim, he joined the legions of Filipino foreign workers fanned out across the globe, sending remissions back to their families. Pizo decided to try working in Saudi Arabia.

Pizo: Until now, a lot of Filipinos are going to not only Saudi Arabia, we call it the Middle East region, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, Oman, Kuwait. When you go and apply for a job and you are accepted, you are gambling with your life, actually.

Were you afraid of them?

Pizo: No. I didn’t have that feeling. Sorry, I’m not bragging about this, but I was never afraid. In the prison, we were fed once a day only. Rice, they sprinkled with sand. How could you eat? But I had to. I would eat sand sprinkled rice. I live. They live, I live. I had this kind of sense of humor.

Pizo: They were torturing me, I was still laughing at them, making fun of them. I didn’t show my emotion. Every Friday I was beaten, whipped actually. Muttawa were the prison guards with their AK 47’s pointing at you. The guy whipping me would be telling me, I’ll kill you. I said, if I die, no problem. He whipped me harder.

In the extended interview, Pizo reads his poem, Whipping Rope.

While he was in Saudi Arabia, Pizo’s father suffered a heart attack, his family needed money, but Pizo was not paid, he couldn’t send money home. Feelings of failure compounded physical abuse. He was not paid for nearly a year, so Pizo led a strike. which led to more whippings, and eventual deportation to the Philippines.

It was not exactly a triumphant homecoming. There was a bus collision on the way from the airport. Pizo lost his short term memory---but turned to some journals he had begun keeping in Saudi Arabia. His doctor advised him to write.

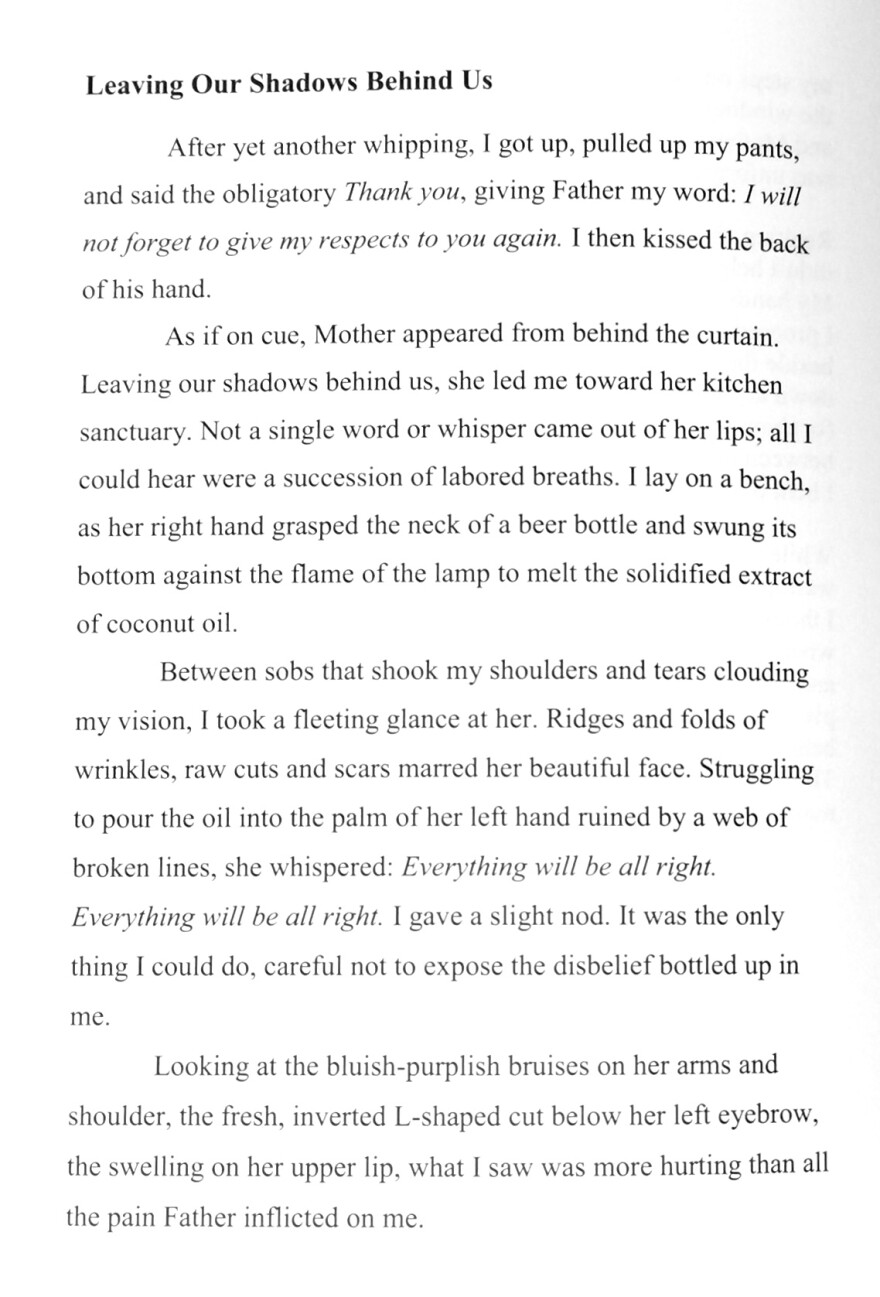

Even more came out: Cruel abuses Pizo and his mother had suffered at the hands of his father. Pizo wondered at his father’s rage until, years later, a neighbor hinted at a clue. All is revealed in the book, and in The Conversation segment.

Through these poems, Pizo talks about forgiveness and redemption. He says this book, Leaving Our Shadows Behind Us, is his redemption from being branded a failure in his hometown, Asingan.

The poems are honest. Poems about being brown manong, about getting circumcised the old way, about eating balut. Pizo has got some calmly scathing poems about Filipino stereotyping and dissing that is still so widespread in Hawai‘i. Pizo writes in English and in Ilocano.

Pizo wouldn’t tell me how and why he came to Hawai‘i 29 years ago—he worked 16 years in DOH vector control here, then, pushed out, he’s been a woodworker, groundskeeper, and security guy, until he was hurt on a construction site this January. All the while, he’s been writing.

Pizo hopes to go back to the Philippines, and share his work there, work with kids, maybe link agriculture and poetry and woodworking---that would be his dream. He would do it here, but says kids in Hawai‘i probably wouldn’t respect him.

The book is Leaving Our Shadows Behind Us on Bamboo Ridge Press.

Pizo will read at the Hawai‘i Book and Music Festival this Saturday, 5/4/19, noon to 1pm.