As the lava flow from K?lauea threatens to hit the town of P?hoa, the potential cutting off of memories is also a concern. As part of our ongoing series, HPR’s Molly Solomon takes a personal look at what that means to people who may never be able to go back.

Craig Shimoda pulls up to meet me in his dusty blue station wagon. I hop in and we drive for about a mile from the main road. He’s taking me to see the P?hoa Japanese cemetery. "A lot of people don't know this is here," says Shimoda.

One of his duties as the President of the P?hoa Nikkei Jin Kai, is to maintain the dozens of graves of Japanese Issei, first-generation immigrants who came to the rural town as plantation workers. One of them was my great-grandfather. But we’ll come back to that later.

Craig and I turn onto a dirt road and drive past a metal gate. "It's beautiful out here," he says as he hops out of the car. "Whenever you come out here it's so peaceful." The cemetery is made up more than 250 graves, many of them marked as unknown. The tombstones that remain are worn, some dating back as early as 1905.

Craig says people have already started to collect tombstones, worrying the lava will take the graves. Others have come to say goodbye to their ancestors for what they fear may be the last time. "I was born in P?hoa in 1937 and I went to P?hoa High School. I've lived here all my life," says Roy Sato, who's come to visit his family grave. "My mom and dad, sister and brother are in this tombstone."

Roy now lives in Kurtistown, the next town over. Prompted by the lava, he’s come back to P?hoa to spend the day cleaning his family grave. He sits down to light incense and places a handful of bright red anthuriums in a vase. "That's why I'm here, to take a picture," Roy says as he places an apple before the altar. "Because once it's covered, it's gone forever"

Roy’s also in town to see his sister and niece, who still live in P?hoa. He plans to walk down the main road and visit some of his favorite spots, including the Akebono Theatre and his old elementary school. "What P?hoa means to me is, you know, we were born here. To see it go under the lava is really sad. But can't fight mother nature, I guess."

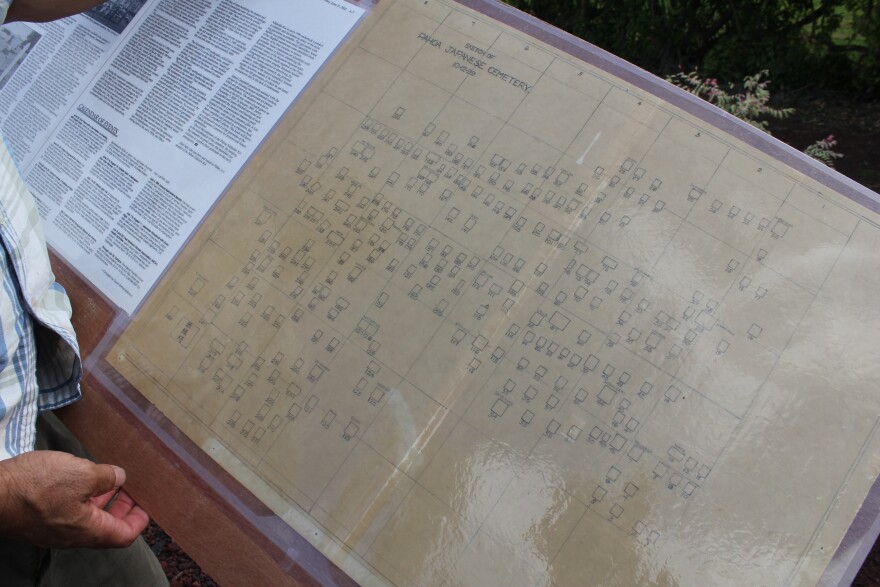

As we head back to his car, Craig pulls out two framed maps from his trunk, detailing the burial plots in the cemetery. The maps are intricately drawn by hand on old parchment paper, each grave is marked with a number that corresponds to a list of names.

My aunt Edith and my mom, Annie, are along for the ride as we visit P?hoa. That's because this town is also where my grandpa is from. They scan the map for a Kiyoshi Yoshiwa, his brother.

"Yeah, there it is...Yoshiwa," Edith says pointing to plot 84 on the map. "My uncle."

Kiyoshi was only a baby when he passed away -- his twin brother Uncle Johnny lived in P?hoa most of his adult life. My aunt used to joke, at age 70—he was probably the oldest bagger at P?hoa Cash & Carry.

Our family roots in P?hoa started with my great grandparents who moved to the Big Island from Hiroshima. Like many young people at the time, my grandfather Eichi Nakao, dropped out of school in the 6th grade to help raise money for the family…working in the sugar cane fields in Puna.

Back in town, I walk through the main drag in P?hoa with my mom. As we begin to talk story, it's clear: family memories are everywhere.

There’s the window Gramps used to sneak into at the Akebono Theatre. Or the time he and his friend got lost in an old lava tube and the whole village went to look for them. And while those memories linger, their physical reminders may not. "If that's wiped out, your family history is gone," my mom says as we walk past shops and restaurants, some already beginning to pack up in anticipation of the lava. "Your memories are wrapped up in these physical things. And when you don't have those, you kind of lose something."

And that’s why this trip is personal. There’s a real purpose to coming back. "Because without those things, you lose that thread," she says. "And I think that's why people go back. They want to see those things, they want to touch those things. When that's gone, I think you really lose a lot — you lose your history." History that many, including my family, want to visit while it’s still there.