The next group of American composers were born several years later than most of the Boston Six, most lived much later, and in style they were more diverse.

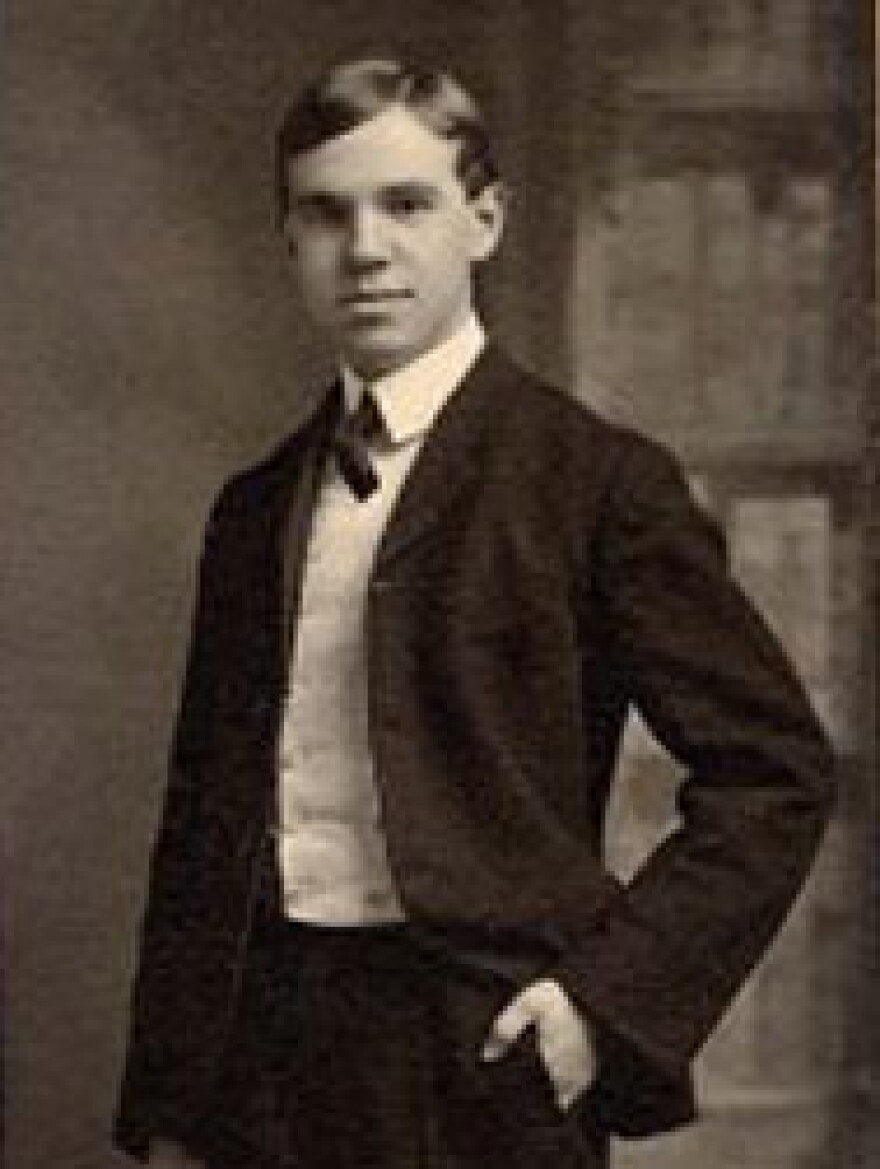

Frederick Converse (1871-1940), the son of a Massachusetts industrialist, studied in Germany, and had George Chadwick as a teacher in New England. He taught for a few years, first at the New England Conservatory and then at Harvard, but by 1907 he was composing full-time. His style was late Romantic but his choice of American subjects made his music more than a mere copy of Richard Strauss. In 1910 he wrote the first opera by an American composer to be staged at New York’s Metropolitan Opera.

Among his most interesting works are “The Mystic Trumpeter,” inspired by Walt Whitman, and “Flivver 10 Million,” about the Model T Ford, which depicts a factory and includes a car horn, deployed by itself at a moment of drama in the music, clearly going for a laugh. Most of his music came in the first two decades of the 20th century, but he composed symphonies in 1923, 1934 and 1940.

Charles Ives (1874-1954) is one of the most unusual figures in the entire history of classical music, the son of a bandleader who learned music from the cradle and studied under Horatio Parker at Yale, then went into the insurance business, invented estate planning, and became a millionaire. He published a book on estate planning in 1918 that made him famous in the insurance business, where people mostly had no idea he had a secret life as a composer. He composed, or revised what he had composed, most of his life, insulated by his fortune from the need to pander to critics or the public.

His music is sometimes beautiful, often dissonant, filled with quotes from popular music ranging from the classics to hymns to patriotic tunes. Ives’ First Symphony, finished in 1902, was a graduation piece. The opening movement touches almost every key while still sounding Brahmsian; the second movement sounds like an American response to the largo from Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony, complete to featuring an English horn.

The middle movement of “Three Places in New England” famously sounds like two marching bands approaching a field from two different directions playing different works in different keys, and there is similar joyous cacophony in the middle movement of his Third Symphony, whose opening movement is sweet-tempered but chromatic, placing unexpected harmonies under snatches of “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.” Fame found Ives in the classical world in the 1950s, when he was old and frail. He is now securely in the repertory despite the great difficulty of performing his works accurately.

John Alden Carpenter (1876-1951) was born in the Chicago area, but studied at Harvard. He studied in Europe, but while other Americans had flocked to Germany, Carpenter wanted lessons from Elgar, finally tracking him down in Rome. He returned to Chicago in 1912 and continued his musical studies but joined his father’s shipping business so, like Ives, he was in music for love, not money.

Carpenter’s music is diverse in style, but well-constructed and witty. His biggest hit was “Adventures in a Perambulator,” 1912, depicting a baby’s ride in a stroller from the baby’s perspective. His 1922 composition “Krazy Kat: A Jazz Pantomine” is thought to be the first classical composition with “jazz” in the title. “Skyscrapers,” 1922, sounds more modern and fits with other Roaring Twenties works inspired by modern machines.

Charles Tomlinson Griffes (1884-1920) might be considered a French Impressionist composer who happens not to have been French, though not all of his works fit this description. Born in Elmira, N.Y., he studied in Berlin, came back to America in 1907, and for the rest of his short life he taught music at a boy’s school in Tarrytown, N.Y.

He died in 1920 at the age of 35. For generations he was represented in the repertory only by Poem for Flute and Orchestra, but there are now recordings of “The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan,” “The White Peacock,” and other works.

Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) is an American composer only by stretching a point. Her father was an American but her mother was German and she was born and raised in England. Her father encouraged musical studies until her professor proposed marriage, then withdrew her from the Royal Academy of Music. She became a violinist, then switched to viola. When her father cut off her funds due to disapproval of her romantic liaisons, she supported herself as an orchestra violist.

She moved to America in 1916, the year she turned 30, and gave a recital of her own works with a cellist, some under her own name, but one work under a male pseudonym. That was the piece praised the most. In 1919 she and Ernest Bloch both entered a composition competition and some critics speculated that “Rebecca Clarke” was a pseudonym for Bloch. It was that inconceivable, in those days, that a woman could compose competently.

In her fifties, married, she stopped composing and performing despite her husband’s encouragement to do so. Her comparatively small output, or that of it which has been recorded, sounds very fine. It does not sound like Ernest Bloch.

(reprinted courtesy of Howard Dicus and Hawaii News Now)